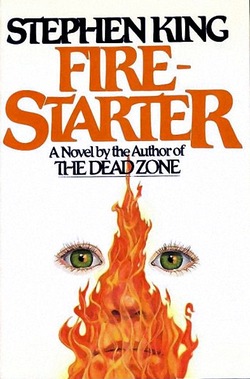

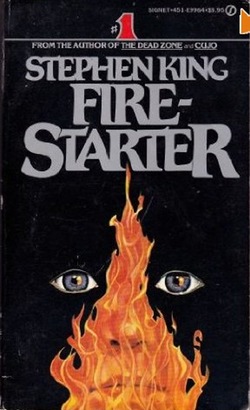

By the time Firestarter came out in 1980, Stephen King was a bona fide phenomena. He was living in his now-famous mansion in Bangor, Maine, he was making more money than he knew what to do with, and his publishing deal with New American Library was making everything better: the binding on his books was better, the covers were better, and they treated him better than Doubleday ever had. Best of all, NAL was better at selling his books. Doubleday had only managed to sell 50,000 hardcover copies of The Stand in its first year. Viking, in conjunction with NAL, sold 175,000 hardcover copies of The Dead Zone in its first year, and Firestarter would go on to sell 280,000. Leaving Doubleday turned out to be the decision that made King a blockbuster author, and despite his massive alcoholism and his brand new cocaine addiction, the books he produced during this New American Library period were among his darkest, leanest, and meanest. They also revealed an essential fact about Stephen King: he wasn’t writing horror at all.

Bill Thompson, the Doubleday editor who discovered King, had been worried that King would be typed as a horror novelist after he submitted ‘Salem’s Lot and again when King told him the plot of The Shining. “First the telekinetic girl, then the vampires, now the haunted hotel and the telepathic kid. You’re gonna get typed,” he reportedly said. To Doubleday, horror was tacky and they had to hold their noses to sell King. Their editions of his books were printed cheaply, had lousy covers, and the higher-ups not only never wanted to wine and dine King, they couldn’t even remember his name, leaving Thompson in the awkward position of having to re-introduce his bestselling author over and over again to the very people whose holiday bonuses were based on King’s sales.

New American Library were paperback publishers and they understood the power of genre. They invested far more heavily in King’s career than Doubleday ever did, not only paying for half the advertising costs on Carrie’s hardcover release, but also paying him advances of $400,000 (Carrie), $500,000 (‘Salem’s Lot), and approximately $500,000 (The Shining) while Doubleday paid King a grand total of $77,500 for his first five books combined. To Doubleday, King was an embarrassment, but to New American Library he was a brand. “‘Salem’s Lot had been read at NAL with a great deal of enthusiasm,” King said in an interview. “Much of it undoubtedly because they recognized a brand name potential beginning to shape up.”

New American Library were paperback publishers and they understood the power of genre. They invested far more heavily in King’s career than Doubleday ever did, not only paying for half the advertising costs on Carrie’s hardcover release, but also paying him advances of $400,000 (Carrie), $500,000 (‘Salem’s Lot), and approximately $500,000 (The Shining) while Doubleday paid King a grand total of $77,500 for his first five books combined. To Doubleday, King was an embarrassment, but to New American Library he was a brand. “‘Salem’s Lot had been read at NAL with a great deal of enthusiasm,” King said in an interview. “Much of it undoubtedly because they recognized a brand name potential beginning to shape up.”

But is there anything beyond marketing that types King as a horror writer? Today, when you look at The Dead Zone (man tries to assassinate political candidate), Firestarter (girl and dad with psychic powers on the run from the government), and Cujo (rabid dog traps woman and child in their car) you realize that with no horror boom to hang them from, with no Stephen King horror brand to emblazon on their covers, these books would probably be sold as thrillers. King himself claims that he writes suspense. Right before Firestarter was released he gave an interview to the Minnesota Star saying, “I see the horror novel as only one room in a very large house, which is the suspense novel. That particular house encloses such classics as Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea and Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter.” And, of course, his own books.

In another interview King stated, “The only books of mine that I consider pure unadulterated horror are ‘Salem’s Lot, The Shining, and now Christine, because they all offer no rational explanation at all for the supernatural events that occur. Carrie, The Dead Zone, and Firestarter on the other hand, are much more within the science fiction tradition…The Stand actually has a foot in both camps…”

So why did the horror label stick?

King writes about characters in extremis, their emotions dominated by fear, pain, and/or helplessness, and he’s excellent at maintaining tension, hinting darkly at unfortunate events to come even in a book’s happiest moments. He also lingers on descriptions of the human body, dwelling on physical details of imperfection and decay (age spots, deformity, decomposition, acne, injuries), as well as reveling in writing about the more physical side of life (sex, excretion, zit popping). His character descriptions are painted in broad strokes, often centered on a physical flaw (dandruff, balding, bad skin, obesity, emaciation), giving many of his characters the appearance of grotesques. He also wrote about teenagers and children a lot, and his lead characters were usually physically attractive.

King writes about characters in extremis, their emotions dominated by fear, pain, and/or helplessness, and he’s excellent at maintaining tension, hinting darkly at unfortunate events to come even in a book’s happiest moments. He also lingers on descriptions of the human body, dwelling on physical details of imperfection and decay (age spots, deformity, decomposition, acne, injuries), as well as reveling in writing about the more physical side of life (sex, excretion, zit popping). His character descriptions are painted in broad strokes, often centered on a physical flaw (dandruff, balding, bad skin, obesity, emaciation), giving many of his characters the appearance of grotesques. He also wrote about teenagers and children a lot, and his lead characters were usually physically attractive.

These intense scenes of sex and violence, his casts of attractive young people, and his emphasis on fear and tension reminded audiences of that other place where sex, violence, tension, and youth overlapped: the horror movie. As King boomed, so boomed the horror genre in film (1973 to 1986 is considered a golden era for American horror movies) and one came to be associated with the other. Comparing King’s writing to movies is something critics have done since the beginning of his career and King himself chalks it up to the fact that he’s an extremely visual writer, unable to commit words to the page until he can see the scene in his head. The link in the public mind between his books and horror movies was cemented when film adaptations of Carrie and The Shining both became widely publicized movies.

The short answer: if it’s marketed like horror, if it reminds people of horror, and if the author is comfortable being branded as writing horror, it’s horror. Even though, as King points out, science fiction would be a better label for many of his books.

Firestarter, the most science fictional of King’s suspense novels, spawned a flop movie and its reputation has become tarnished with time. Which is too bad because it’s unique among King’s books in that it finally tackles his biggest blind spot: sex. Started in 1976, King abandoned Firestarter because it reminded him too much of Carrie. With a main character based on his ten-year-old daughter, Naomi, King was fascinated first by pyrokinesis and then by the idea of a character like Carrie White passing her psychic abilities on to her daughter. He was also becoming more and more liberal. Descended from generations of blue collar Republicans (he even voted for Nixon in 1968) King started drifting to the left in university, and wound up on the Democratic side of the spectrum. It’s hard not to see that progression in The Stand, The Dead Zone, and Firestarter as they revel in broad depictions of an uncaring military-industrial complex, corrupt right-wing politicians, and black ops government departments run amuck.

Firestarter, the most science fictional of King’s suspense novels, spawned a flop movie and its reputation has become tarnished with time. Which is too bad because it’s unique among King’s books in that it finally tackles his biggest blind spot: sex. Started in 1976, King abandoned Firestarter because it reminded him too much of Carrie. With a main character based on his ten-year-old daughter, Naomi, King was fascinated first by pyrokinesis and then by the idea of a character like Carrie White passing her psychic abilities on to her daughter. He was also becoming more and more liberal. Descended from generations of blue collar Republicans (he even voted for Nixon in 1968) King started drifting to the left in university, and wound up on the Democratic side of the spectrum. It’s hard not to see that progression in The Stand, The Dead Zone, and Firestarter as they revel in broad depictions of an uncaring military-industrial complex, corrupt right-wing politicians, and black ops government departments run amuck.

This book reads like a paranoid, left-wing fantasy on speed. Kicking off with ten-year-old Charlie McGee and her father, Andy, on the run from a government agency called The Shop, we’re not 20 pages in before they’re run to ground and barely slip away. It turns out that Andy and his wife were dosed with an LSD-esque drug called Lot Six in a government experiment in the 60’s. It activated their latent psychic powers, which they have passed on to their daughter, Charlie, who can start fires with her mind, but has been expressly forbidden to do “the bad thing” by her parents. Mom was killed by The Shop, and Andy is armed only with the power to control minds, at the cost of brain damage every time he “pushes” someone.

Cornered again, Andy convinces Charlie to cut loose with her powers and she turns a peaceful farm into a raging inferno, killing dozens of Shop agents in their escape. A few months later, they’re captured by John Rainbird, a death-obsessed Shop operative with a mutilated face. The last third of the book chronicles Charlie and Andy’s captivity on The Farm (there are a lot of farms in this book), which is Shop HQ where Redbird begins a slow mind-game, pretending to be a simple orderly who befriends Charlie and gets her to cooperate with the Farm’s research. Separated from his daughter, Andy becomes an overweight pill junkie, and eventually it all ends in a horse barn with Charlie realizing the depth of her betrayal by Rainbird, destroying the Farm, and witnessing her dad’s death. It sounds straightforward, but King was firing on all cylinders at this point in his career, and so it’s anything but.

Cornered again, Andy convinces Charlie to cut loose with her powers and she turns a peaceful farm into a raging inferno, killing dozens of Shop agents in their escape. A few months later, they’re captured by John Rainbird, a death-obsessed Shop operative with a mutilated face. The last third of the book chronicles Charlie and Andy’s captivity on The Farm (there are a lot of farms in this book), which is Shop HQ where Redbird begins a slow mind-game, pretending to be a simple orderly who befriends Charlie and gets her to cooperate with the Farm’s research. Separated from his daughter, Andy becomes an overweight pill junkie, and eventually it all ends in a horse barn with Charlie realizing the depth of her betrayal by Rainbird, destroying the Farm, and witnessing her dad’s death. It sounds straightforward, but King was firing on all cylinders at this point in his career, and so it’s anything but.

Full of actions setpieces so vividly described that they turn into a kind of surrealist poetry (exploding chickens running across a yard, guard dogs driven insane by heat and attacking the people they’re supposed to protect), it’s also spiked with subjective descriptions that that attain a funky beat poetry grandeur (“Never mind. Sit a little longer. Listen to the Stones. Shakey’s Pizza. You get your choice, thin crust or crunchy”). King has been accused of shying away from sex (Peter Straub once famously said, “Stevie hasn’t discovered sex yet.”) but if Firestarter is anything it’s the story of Charlie’s sexual awakening.

There are few things more fraught than the relationship between fathers and daughters, and pop culture has devoted enormous amounts of time and energy to showing the discomfort fathers feel with their daughter’s sexuality, from questioning who they date to controlling what they wear. Charlie starts the book as a little girl, holding her father’s hand, uncertain of what to do without being told. By the end of the book her father is dead, she’s not only in full control of her pyrokinesis but it’s far stronger than anyone thought, and she’s on her way to New York City to take down the government by blowing the whistle to Rolling Stone, of all places.

There are few things more fraught than the relationship between fathers and daughters, and pop culture has devoted enormous amounts of time and energy to showing the discomfort fathers feel with their daughter’s sexuality, from questioning who they date to controlling what they wear. Charlie starts the book as a little girl, holding her father’s hand, uncertain of what to do without being told. By the end of the book her father is dead, she’s not only in full control of her pyrokinesis but it’s far stronger than anyone thought, and she’s on her way to New York City to take down the government by blowing the whistle to Rolling Stone, of all places.

Sex and fire are linguistically joined at the hip (“burning passion” “the fires of desire” “smouldering eyes” “smoking hot”) and it’s the dirtiest of Freudian jokes that Charlie is told that her ability to start fires is “The Bad Thing” and she mustn’t do or she’ll hurt her parents. Things go from subtext to plain old text once she’s taken in hand by John Rainbird who yearns to “penetrate her defenses,” “crack her like a safe,” and to kill her while looking deeply into her eyes. “It’s a sexual relationship,” King later said about the friendship between the two characters in an interview. “I only wanted to touch on it lightly, but it makes the whole conflict more monstrous.”

As her inhibitions surrounding the use of her powers fall, Charlie revels in her newfound strength, which earns her special privileges and makes her the center of attention from every man in the book. The point is made repeatedly that unless she’s controlled or killed her powers could destroy the world, a clichéd fear about female sexuality (once they start, they just can’t stop). As Charlie’s sexuality becomes more and move liberating and overt (including dreams of riding a horse, naked, to meet John Rainbird), the sexual desires of the men controlling her life become more covert and self-destructive. Andy starts using his “push” to try to escape, but it sometimes sets off ricochets in the subconscious minds of his victims, unleashing their secret obsessions and sending them into self-destructive feedback loops.

As her inhibitions surrounding the use of her powers fall, Charlie revels in her newfound strength, which earns her special privileges and makes her the center of attention from every man in the book. The point is made repeatedly that unless she’s controlled or killed her powers could destroy the world, a clichéd fear about female sexuality (once they start, they just can’t stop). As Charlie’s sexuality becomes more and move liberating and overt (including dreams of riding a horse, naked, to meet John Rainbird), the sexual desires of the men controlling her life become more covert and self-destructive. Andy starts using his “push” to try to escape, but it sometimes sets off ricochets in the subconscious minds of his victims, unleashing their secret obsessions and sending them into self-destructive feedback loops.

For Dr. Pynchot, the psychiatrist in charge of Andy and Charlie, the ricochet involves an incident of sexual humiliation at the hands of his fraternity brothers. He becomes obsessed with the “vulva-like” opening of his new garbage disposal and winds up dressing in his wife’s underwear and killing himself by shoving his arm into it while it’s running. The head of the Farm, “Cap” Hollister, earns a ricochet that’s slightly more subtle, but a lot more symbolic, becoming doddering, distracted, and obsessed with slithering, phallic snakes whom he imagines are hiding everywhere, waiting to leap out and bite him.

Charlie, on the other hand, is obsessed, as are many young girls, with horses, and her fascination with their freedom and power is conveyed through dreams of riding bareback and out of control through a burning forest. One of the book’s most powerful images is of Charlie standing in front of a burning barn after wild horses have burst through its wooden walls, laying waste to the might of the United States military, her dead father behind her, freedom somewhere up ahead. It’s about as poptastic and tacky and powerful an image of a young woman’s sexual awakening as you could find, so resonant that it should be airbrushed onto the side panel of a van.

Charlie, on the other hand, is obsessed, as are many young girls, with horses, and her fascination with their freedom and power is conveyed through dreams of riding bareback and out of control through a burning forest. One of the book’s most powerful images is of Charlie standing in front of a burning barn after wild horses have burst through its wooden walls, laying waste to the might of the United States military, her dead father behind her, freedom somewhere up ahead. It’s about as poptastic and tacky and powerful an image of a young woman’s sexual awakening as you could find, so resonant that it should be airbrushed onto the side panel of a van.

Far from being one of his “meh” books, approaching Firestarter with an open mind reveals it to be one of King’s most fascinating. He’s out of his self-proclaimed comfort zone here, exploring the sexual awakening of a character based on his own daughter, and celebrating power, freedom, and liberation in a way his books rarely did. It was the centerpiece of his mid-career trio—The Dead Zone, Firestarter, Cujo—that showcased King at the height of his powers…but it was really just a warm-up for Cujo.

Grady Hendrix has written about pop culture for magazines ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today. He also writes books! You can follow every little move he makes over at his blog.

I recently reread Firestarter for the first time since high school and was amazed by what a powerful novel it was. MAybe it has to do with being a father of an eleven year old now, but I found the relationship between Charlie and her father to be one of the tightest in King’s career.

Not only that, but it nicely rounds out King’s initial “Haunted Kids” stories, capping off the Carrie, Danny, Mark team with Charlie in full command of her abilities. It also stands as a nice counterweight to Carrie, with the young girl not succumbing to destruction, but overcoming it.

I am so glad King wrote all of these before he began shoehorning “Dark Tower” mythology into everything he wrote, because they all exist nicely in the same world without being too explicit about it. I like to think that the government saw a missed opportunity in the Carrie White case and really tightened up on Charlie.

What’s really interesting is how bumbling the Shop is portrayed as I recalled them being this super smart organization, when in fact they are a bunch of underfunded barely competent suits who fall to pieces at the slightest hint of danger.

So, yeah, I really liked Firestarter. Thanks for the great writeup.

BJ, a great many of King’s big bads end up being bumbling incompetents after all is said and done. One of the themes running through a majority of his books is that, while scary and dangerous, evil can be defeated easily.

I haven’t read this since high school but Batman Jesus has a point…my daughter’s 16 now and I’ve noticed that all parent/kid-centric movies & books have a bigger impact on me now that I’ve got kids of my own. I think it’s time to revisit Charlie myself.

Edit – Soless nailed it. I’ve always said that *spoiler alert!* Flagg in particular went out like a punk.

Agreed about the bumbling part, but what I love about Firesarter is it shows you their incompetence from the beginning. In later books though (I’m looking at YOU “Dreamcatcher”) the government is made a much more sinister presence. Much more “All seeing.” As opposed to The Shop who were a bunch of mid-level beauraucrats with guns.

In my reread, I find myself liking the hardscrabble world of early King and his young portagonists. If Carrie, Mark, Danny and Charlie had joined forces . . . well, I’d read that book.

“If Carrie, Mark, Danny and Charlie had joined forces . . . well, I’d read that book.”

Would someone write this, please?

King once said in an interview that the second inspiration for Firestarter was him wondering what would happen if Carrie White and Danny Torrance got married and had a kid. So maybe he’ll wind up writing it himself…?

@1 What’s really interesting is how bumbling the Shop is portrayed as I recalled them being this super smart organization, when in fact they are a bunch of underfunded barely competent suits who fall to pieces at the slightest hint of danger.

The idea that cloak-and-dagger conspiracies are well-oiled machines employing hundreds of super-competent assassins comes to us from Ian Fleming and Robert Ludlum, the pulp stars of two generations prior to King. But King’s early years as a writer and as a father coincided with–

1. the Watergate trials, providing a lifetime supply of material for strange, cranky, petty yet dangerous villain characters in the form of Nixon and his crew;

2. the Church Committee hearings revealing the MKUltra program, which, despite being a secret government group that abused and killed people in the pursuit of science-fictiony-sounding goals, was also kind of a flaky and poorly contained operation.

The Shop, Greg Stillson, Flagg’s henchmen, et al., all make perfect sense in that context. Near the beginning of Firestarter, secret agents torture and murder a housewife and barely bother to conceal the body, but we don’t see that happen; the act of covert political terror that King devotes the most pages to is when two not-very-bright thugs steal a sack full of mail at gunpoint from an outraged elderly postman with a flatulence problem in Podunk, NY. King writes that scene comically but there’s some real anger underneath it, at the idea that we could be terrorized by people who aren’t just evil, but evil fools.

EliBishop – Very good point. And, I love that scene with the mail. I seethed with rage for the postal worker because he was so much smarter than those two.

I dunno, Batman, Charlie was one I always hoped would pop up in the Dark Tower series, especially as the characters with psionic powers were introduced into the series. I just really always wanted to know what happened to her.

This article has really made me want to reread this again, especially as I missed all these references to Charlie’s burgeoning sexuality(now she’s Danaerys is my mind) probably because I wasn’t too much older than Charlie when I read it.

Young women’s sexuality and men’s attempts to control it become a common topic in King’s books after this, like Beverly and her father in IT. King handles it with a forthrightness that this young woman appreciated growing up, as everyone else handled the topic more cautiously than a ticking bomb, or emphasized it as something terrible that must be avoided.

Thanks for this article. Of King’s novels, Firestarter is by far my personal favourite. The scene with the Postman is one that I’m often reminded of. It’s been a while since the last reread but I remember identifying with the feeling of disillusionment he was left with after the thoughtless thuggery of the Shop agents.

Eli Bishop @6 writes:

> King writes that scene comically but there’s some real anger underneath

> it, at the idea that we could be terrorized by people who aren’t just

> evil, but evil fools.

That totally resonates with me. There was a murder here some years ago where – I think – a burglar was surprised by someone returning home and killed him. In his court testimony the burglar said:

“He was being a smartass so I tortured him a bit.”

If that had been fiction I would say that is one of the best and scariest bits of character building I’ve ever read.

Whoa, I never thought about the sex thing. I’ve got to read the book again now. . .though it might become as awkward as you-know-that-part in It. >_>

No, nothing can be as awkward as the “You-Know-That-Part in IT! I understood the need for it, I understood the point he was trying to convey. But that doesn’t change the fact that it was awkward, uncomfortable reading it (as it must have been writing it, one can hope) and probably could have been done differently. But that’s what’s pretty good about King’s books. Not all of it is comfortable and not all of it is happy and makes sense because Life doesn’t make sense, life is more often than not awkward and uncomfortable and things happen in it that we wish never happened. Kinda like the ending of the Dark Tower series. I won’t give anything away, I’ll just say that I hated it, but I wouldn’t have it any other way.

I don’t think DT could have ended any differently either. He did try to warn us too.

Yeah, but does anybody even know anybody who DIDN’T read past the warning? And agreed, there really wasn’t any other way to end it.

I had a friend who didn’t, which sucked, as we spent years discussing DT and when she stopped like Steve told her to, we couldn’t finish.

Wow, that’s some kind of self control. There’s no way I could’ve just stopped reading.

I started reading this article and laughed at “New American Library was making everything better: the binding on his books was better, the covers were better,” I looked for spoiler as second paperback I was reading was missing last few pages (fallen out) which I failed to notice while reading.

I read firestarter for a 6th grade project, im 11 and it was amazing to read it! I honestly would read it again if i wasn’t lazy… now im reading 11.23.63, and its just as good! but for the 1 unneccisary part that Al got lung cancer its still good. but firestarter will always be a favorite of mine.

i will always love firestarter. and idk why i made this blue :3

aww it didnt come out the same color as i typed it in :(

Charlie is 7 years old when the book starts and 9 when the book ends.

Excellent analysis of what is probably Mr. King’s greatest novel.